(From the archives: An edited version of this story was translated into French and published in the now-defunct magazine Asies in 2011.)

Pokhara & Kathmandu (Nepal): Offering a spectacular panorama of the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri mountain ranges, Pokhara airport can surely make into the list of the world’s most beautiful airports. Situated in one end of the Pokhara Valley, with the snow-capped mountains set against the blue winter sky and helicopters buzzing around like bees, the airport is a fitting welcome to Nepal’s second most popular tourism destination after capital Kathmandu, 200 km away.

A few metres away, in his first-floor quarters above the Lodrik Welfare Fund office (for former Tibetan freedom fighters), Tamding Wangyal sat telling a rosary. “My last wish is to die in my own land,” said the former chairman of the Lodrik Welfare Fund, who retired in 2010 after serving 32 years in the office. “A big house. A big field… It’s like a picture, still fresh in my eyes,” said the 82-year-old former Kham warrior recalling his Tibet home. “Though most people I knew have passed away, I last heard that my niece and nephew are still there,” he added sipping hot Tibetan tea. The noise of aircraft landing and taking off mix with the urgent pressure-cooker whistles coming from the kitchen where lunch is being prepared.

Wangyal

Wangyal and others—monks, traders and peasants—had left their homes in Kham region of Tibet with food and nothing else hoping they would be back soon after the liberation war is over and Tibet is regained. That “soon” has now stretched to more than 52 years of refugee life in Nepal, with friends and relatives, many of them dead, scattered all over Nepal and India.

The ‘good’ Chinese

Early Chinese soldiers began moving into Tibet in 1949-50. “They used to wear chubas like the Tibetans and begged in street corners,” Tashi Dhondup, popularly known as Gen Tashi, at Pokhra’s Peljorling Refugee Camp said recalling from his childhood memories of ‘Chinese beggars’. “It was much later we understood that they were not beggars after all. They were Chinese spies,” he still seems surprised. His eyes twinkle as darkness engulfs his home—one biggish room with two single beds placed at right angles, one big table at the centre, an LPG double-burner stove on a side table set against the wall and saucepans hanging from the wall.

Gen Tashi, “one year younger than His Holiness (14th Dalai Lama)”, was about 10 years old when the Chinese began trickling into his native town Charakham. He was the only son of his peasant father, who died when he was still a child. He later went on to become a general in the resistance army, was trained by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and became a trainer at the Mustang camp in Nepal.

“The Chinese were very nice at first,” he said. “They helped farmers in the fields. Chinese employers even paid more money than local Tibetan employers.”

There was a road being made between Chamdo and Lhasa, recalled Gen Tashi. “It was later that we realised that the road was not for the benefit of the Tibetans, but the Chinese.”

The experience of the Tibetans in the hands of tyrannical Chinese has also been very well documented by Anthropologist Carole McGranahan in her book Arrested Histories. “When the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) first came to Tibet, the soldiers and civilian officers not only paid for their food, lodging, and animal transport but also gave presents, clothing, and generous bags of silver coins, called ta yang in Tibetan, to the Tibetans,” she has written. (Page 67)

Reign of fire

Soon the Tibetans found Chinese interference intolerable. The egalitarianism that the Chinese wanted to force down the throats of the Tibetans was far from welcome. The Chinese not only sought to change the socio-political structure but were also against religion. What hit the Tibetans hard was the attack on their religion.

On October, 1950, the governor of Chamdo, Ngabo Ngawang Jigme, surrendered to the Chinese (Arrested Histories, Page 45). In the ensuing mayhem and confusion among government officials in Lhasa as to how to respond to the situation, on November 17, 1950, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, was proclaimed the spiritual and temporal head of the Tibetan state at the premature age of 16. In normal course, he would have assumed the responsibility at 18.

Negotiations with Bejing began, and on May 23, 1951, the much-contested Seventeen-Point Agreement, or Agreement of the Central People’s Government and the Local Government on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, was signed. The Tibetan government held that the agreement was signed “under duress” because the delegation headed by Ngabo Ngawang Jigme was not allowed to consult with the Dalai Lama or the Khasag (cabinet). The Agreement laid down that the Tibetan people shall “return to the big family of the Motherland the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and that the local government of Tibet shall actively assist the PLA to enter Tibet and consolidate the national defences.

Uprisings in Kham began in 1955-56. “They started kidnapping our monastic heads and other leaders. They tried to buy our educated folk and those who refused to be bought were tortured and killed,” Gen Tashi recalled. By mid 50s monasteries became prime targets of Chinese air attacks and very soon Lithang, Chatreng, Nyarong and Bathang became battlefields of bloody wars, of scenes that the peace-loving Tibetans had never imagined before.

However, March 10, 1959 is regarded as the official Tibetan Uprising Day. On this day thousands of Tibetans voluntarily gathered at and encircled the Potala Palace residence of the Dalai Lama to prevent him from leaving or being taken away by the Chinese army. The situation was fuelled by rumours that the Chinese authorities were planning to arrest the holy man during his visit to a cultural programme at the PLA headquarters where he was invited.

Four rivers and six ranges

“Here there was a pile of stones, just next to the stack of firewood to the left of the main gate,” Gen Tashi draws in a piece of paper a sketch of his Charakham house from his memory, unscathed by age. “Here we kept the horses and here, right behind the house, the livestock. And to the right, we had a huge, huge field.”

Gen Tashi

Kham, traditionally known as Chushi Gangdruk meaning four rivers and six ranges, is one of the three regions of Tibet, the others being Amdo and U (U-Tsang and U-Ngari). It is characterised by a rugged terrain cut across by mountain ridges and rivers. In Arrested Histories McGranahan quoted a Khampa warrior as saying: “U is the place of the best religion, Amdo of the best horses, and Kham of the best people”(Page 50). The image of the Khampas is that of honest, simple, plain-speaking and loyal people, though socially unpolished. They are known as fearless and also “dangerous”.

It is from this region that the resistance army got its name—Chushi Gangdruk—and the Khampas made the majority of the guerrilla force. The name of the resistance force was suggested by Trijang Rinpoche, the Dalai Lama’s junior tutor, (Arrested Histories Pg 96) who did a mo (divination) and suggested a Kham-focussed name.

McGranahan describes in her book how the resistance army took shape behind the scenes of an ostensibly religious event. At a time when there was widespread turmoil and devastation, Khampas fled to Lhasa and came to Dalai Lama seeking protection and religious guidance. Traders from Kham and Amdowa requested the Dalai Lama to perform two powerful Buddhist teachings, Kalachakra and the Lamrim Chenmo, to bless those participating or sponsoring the rituals and the whole of Tibet. In turn, the traders would make ritual offerings, including a gold throne for the Dalai Lama as a special gift. As preparations of the long-life ceremony and construction of the throne got underway, so did the covert exercise of forming a resistance group. McGranahan writes—“The golden throne thus served two purposes: to repay the kindness of the Dalai Lama and to secretly facilitate the formation of the new political and military group by providing cover for their frequent meetings.” (Page 96)

Thus, was born Chushi Gangdruk resistance army under the aegis of Andrug Gombo Tashi, in whose home the first meeting was held in February 1958. The formal announcement was, however, made on June 16, 1958. The move got Tibetans under one umbrella and as the news of its formation spread, it grew in strength.

“I was in Chamdo during that time and was clueless about all that was going on in Kham because in Tibet of those days the region was virtually cut off and news hardly came,” said Tamding Wangyal, taking a pause from telling a rosary. Wangyal from Lithang in Kham had quit monkhood after he turned 18 and taken up trading. Being youngest of three sons, following the tradition, he was sent to the monastery at seven. “Some seven-eight monks from Chamdo had gone to Lhasa and they brought the news that Lithang monastery was bombed and that the Chinese army had wreaked havoc in the whole of Kham.”

He sent messages to his family but got no reply. “I presume all of them got killed.” With whatever money he had he immediately bought an “American” gun and joined Chushi Gangdruk.

Lama’s Flight

Jampaling Tibetan refugee resettlement area is only about 25 km from Pokhara, but far removed in terms of development. “Look, this is the kind of place the Nepal government has given the Tibetans to settle as part of its resettlement and rehabilitation plan after they surrendered their weapons,” Tsewang Dolma, President of the Regional Tibetan Youth Congress and daughter of a former freedom fighter, said while crossing a rickety bridge across a gorge. After a trek of a little less than a kilometre from the nearest motorable road and across a gorge, navigable only in fair weather, Jampaling appears, like most of Pokhara, in all its exquisite beauty with the snow-capped Machhapuchhre (meaning fish tail) mountain overlooking small banana plantations and unkempt, weed-invaded fields.

Lobsang Choephel, popularly known as Gombo, is seated in his favourite perch under the tree in front of his quarters. Gombo, from Dragyab village in Kham doesn’t remember his parents who died when he was very small. With no one to look after, he became a monk at the age of 12. When he turned 18 moved to Drepung Loseling monastery in Lhasa.

Gombo

“I was at the Drepung Loseling when we got to hear about the risk to the life of His Holiness,” he said. He was among the 41 monks from the monastery to join the Chushi Gangdruk. “We had earlier made a divination to our protector deity, Tsungma, asking whether we can join Chushu Gangdruk or not. The deity had said no and asked us to wait. On hearing about the developments at Norbulingkha (Potala Palace) where His Holiness lived, we made another divination. This time the deity asked us to leave immediately and we followed the orders,” he added, recalling the events soon after the March 10 uprising.

Thousands of people had surrounded the Dalai Lama’s residence forming a security ring. “Inside, bodyguards had formed a tight security ring around the Dalai Lama, who was accompanied by some high Lamas. His Holiness wore a sombre look,” he recalled from his first visit to the Potala Palace.

On March 30, 1959, too, it was business as usual inside Potala Palace even as thousands of people continued to stand guard outside. It was a secret mission. “We knew what was going to happen, but we took an oath in front of food that no one would give out the secret to anyone,” said the monk-turned-warrior, breaking into a tooth-less grin.

“After sunset, His Holiness appeared wearing clothes off normal people—brownish chuba, long boots, a woollen cap and dark glasses. It was quiet and dark when they left. I felt very sad,” the toothless grin is no more. “We stayed at the monastery going about the normal business as if the Dalai Lama was still inside. After five-six days, the Chinese began bombing the monastery thinking His Holiness is still inside. The ground shook. They continued shooting and bombing an entire day when we decided to flee the monastery. A lot of people had gathered outside despite the bombings. We told them that His Holiness has left. Many just did not believe us.”

Thousands of Tibetans were reportedly killed in the bombings. Forced to take up arms against the Chinese, the monk joined Chushi Gangdruk soon after, and was in the first batch that trained under CIA-return trainers in Mustang, near Pokhara in Nepal.

The War

The whole of Tibet was plunged into a chaos even as people from all walks of life came forward to join the Chushi Gangdruk to fight the Chinese might.

“I was confident nobody could kill me,” said Wangyal, point his finger with the same hand in which he held the rosary. “I don’t remember how many Chinese I killed, but every time I would set out with a promise ‘I will kill as many Chinese people as I can kill today’.”

On the other hand, Gombo and other monks were fleeing, and fighting the Chinese at the same time. “We were carrying guns, bows and arrows, and no food. We crossed village after village, sometimes on horseback and sometimes on foot. The Chinese were everywhere. They were shooting us from the helicopters above and also dropping bombs in the villages.”

“Being monks, we were used to vegetarian food habits, but when it became a question of our survival, we were forced to eat yak meat,” he added.

Gen Tashi’s job profile was that of a messenger. “I had to carry messages for the leaders. I had to keep a tab of the Chinese movements and keep our leaders informed accordingly. I was the one to go to bed last and the first one to rise up.” Not just that, “I also would motivate the youths to join the Chushi Gangdruk.”

However, soon the inexperience of Chushi Gangdruk fighters and the lack of resources began to take a toll and by April end 1959, founder leader Andrug Gombo Tashi decided that the resistance army had to cross over to India to regroup and continue the fight.

Exiled

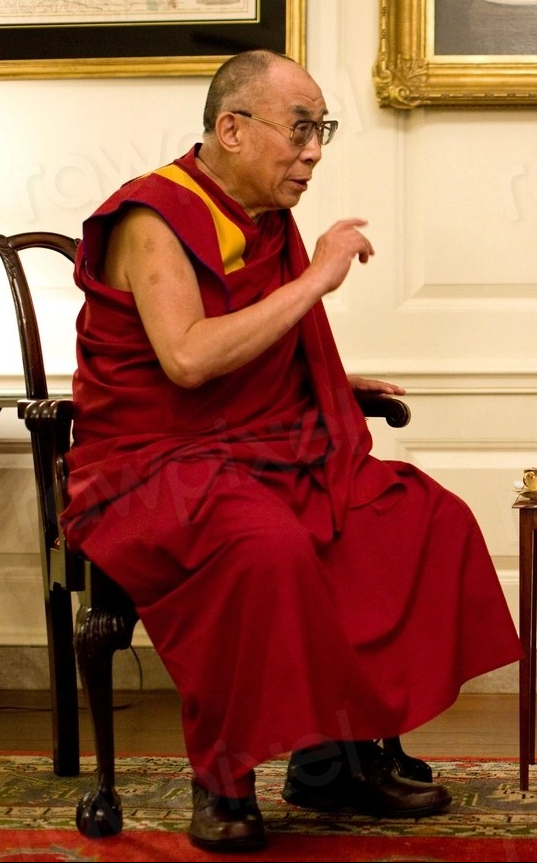

The Dalai Lama

Soon after the Dalai Lama’s flight to India, the Tibetan government-in-exile was established in April 1959 in Mussoorie. In May 1960, the Tibetan government-in-exile was moved to its present headquarters in Dharamsala in northwest India. The exile government governs about 120,000 Tibetans living outside Tibet, such as India, Nepal, Bhutan, US, Europe and Canada.

After the Dalai Lama’s escape, thousands of Tibetans (some estimates put it at 80000) crossed over to India as refugees, many of them taking the same route as the Dalai Lama, ie via Arunachal Pradesh and Assam in northeast India. India government set up transit camps for the refugees in Misamari and Bomdila. Not used to the hot and humid Indian climate, soon death and disease resulted and many of the refugees began moving to the higher altitudes of Sikkim where they got jobs of building roads.

At the border the Chushi Gangdruk soldiers were apprehended, and their weapons confiscated, something which the Khampas did not like. “We had such lovely guns, we had give them all away to the Indians,” said Wangyal.

“Once in India, we were dispersed in different areas— those below 25 years of age were sent to schools, the monks were sent to monasteries and the able-bodied youths were employed in road-making,” he added. Wangyal himself spent some months building roads in Sikkim. “But, there were many who did not want to build roads and wanted the weapons back, but in vain. I joined a group of 500 such men and left for Mustang in Nepal where we heard that training for Chushi Gangdruk will be held.”

Enter, CIA

“They put us on a plane, and I don’t know how long they flew, seemed like two-three days,” Gen Tashi said recalling how he landed in Colorado, US, to get trained by the CIA in 1960. He was 26 then and had spent about two years in Chushi Gandruk already. “The place looked very similar to Tibet. It was only after landing that we got to know that we were in the US.”

The first thing that Gen Tashi and others were told was “In three months you have to finish training of three years!” Gen Tashi was one of the 26 men trained in the US to lead the Mustang force.

“We were taught how to read maps, use campus, do mathematical calculations, how to make and use bombs,” Gen Tashi said. However, what he found most difficult was writing applications. “This required learning and I had never been to a school.”

He found the trainers very kind and inspiring. He still fondly remembers two trainers who introduced themselves as Tony, who taught him how to carry out researches, and Mark, who taught him how to use guns. “After three months a shooting competition was held, in which I got the first prize,” he recalled. As a prize he got a cigarette lighter, which he sold off to a friend, Rara, because he did not smoke.

From 1958 through 1964, several hundred Tibetans attended CIA training camps in the US. At Camp Hale, named Dumra, or garden by the soldiers, CIA officials trained the Tibetans in a range of guerrilla warfare techniques, including paramilitary operations, bomb building, map making, photography, radio operation techniques, courses in world history and politics, and intelligence colleting. (Arrested Histories Page 132)

Mustang

Mustang, meaning fertile plain in Tibetan, is the former kingdom of Lo and is now a part of Nepal in the north-centre part of the country and shares borders with China. The Kingdom was overthrown the same year as the Kingdom of Nepal, 2008.

The trained soldiers were despatched in groups. “I was air-dropped in Japan. From there I went to Mustang via East Pakistan (Bangladesh) and Siliguri in the north east of India, in the journey that took two days,” Gen Tashi said. Both Wangyal and Gombo had reached Mustang by then and were trained under Gen Tashi.

Gen Tashi said he began training in the autumn of 1961. “Initially they did not have any weapons, so we only taught physical exercise and things like how to hide.”

Weapons were dropped in 1962. Wangyal was one of the soldiers who sneaked inside Tibet to collect the consignment of dropped weapons. “We were about 700-800. Some of them carried food and provisions while the rest were to carry back the consignment of weapons. We would sleep in the day and walk in the night till after two-three day’s trek we reached a barren land,” Wangyal recalled, keeping aside his rosary on the table. “It was well past midnight when one big helicopter came there, circled the area and went back and then came back again. Weapons enough for 600 soldiers were dropped. There were guns, bows & arrows and bombs.”

Gen Tashi held the training sessions three times of a day. “In the morning, I taught them maths and mapping. In the afternoon I taught how to use the gun and communications. And, the evening again, I taught them how to use the gun and bomb-making.”

Attacks started in 1962. “This time we were better organised. We went in groups of 50s. Acting on intelligence inputs we would study the movement of the Chinese. We would them ambush them and fight for 15 minutes before returning to our positions. Soon the other group carried on with the offensive,” Wangyal said.

“I was good at throwing bombs,” says former monk Gombo, his toothless grin at its widest. “I was an expert in blasting bridges. I remember blasting two Chinese trucks.”

Surrender

“It was otherwise a smooth operation,” said Tamla Ukyab, former Under Secretary of Nepal’s home ministry who oversaw the 1974 surrender of the Chushi Gangdruk. He was based at the Royal Palace in Kathmandu and was involved in the planning of the operation of Khampa disarmament with King Birendra. As a special officer, he visited the Mustang several times.

“The plan was to finish the operation before the coronation of the King in 1975,” he said at his house in upscale Kuleshwar, Kathmandu. “Our target was before the winter of 1974.”

Ukyab

Ukyab said a rehabilitation and resettlement package was worked out and an ultimatum issued to the Chushi Gangdruk asking them to surrender. “We began to move in the army in March-April. The surrender was smooth and we tried not to use force. But leader Gyato Wangdu and a few others did not surrender and tried to escape. After 25 days we ambushed them and in far west and all of them got killed. By July, the operation was complete.”

None of them–Gen Tashi, Wangyal or Gombo–would surrender. They were not afraid of being killed, nor did they have any interest in the rehabilitation package offered by Nepal. What brought all the brave khampas down on their knees was the word of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. He sent out a taped message asking them to lay down their weapons.

“I did not believe when I heard that we have to surrender,” Wangyal recalled, sipping Tibetan black tea. “Then they played a recorded message from His Holiness. And I surrendered.”