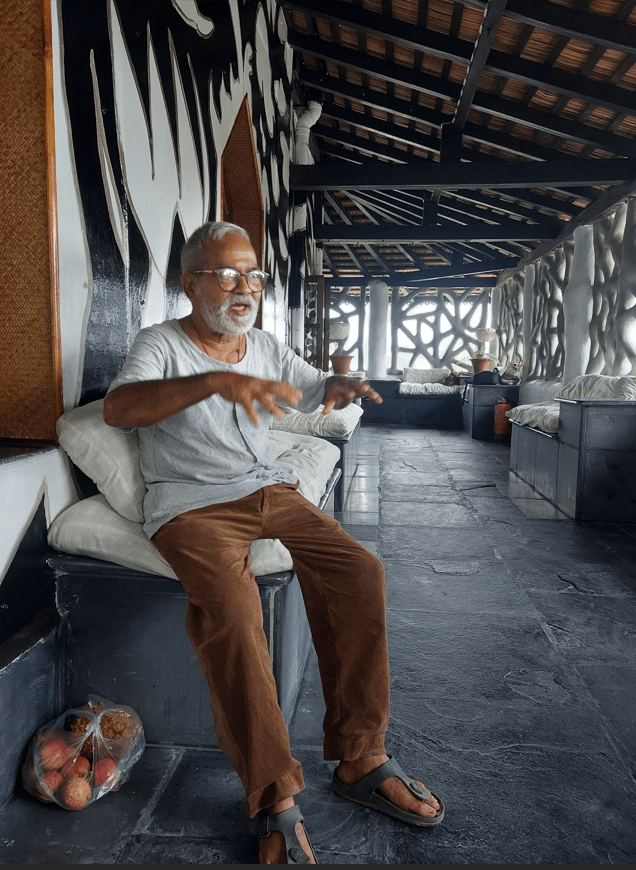

Once in a while, we come across people who make us pause, think, and question the ways of the world. Bidyut-da is one such person. I spent some time with him last month, and since then have been meaning to share my thoughts about the pleasant autumn afternoon. Finally, here it is.

Bidyut Roy is an artist-architect from Santiniketan, Bolpur, and is famous for his homes made of natural materials like clay, bamboo and stone. I call him an artist-architect because his works of architecture are so much the expression of his artistic self. His structures are actually exquisite works of art, with intricate detailing and organic forms. Blending aesthetics with function, he creates artworks one can inhabit.

I first met Bidyut-da in Sundarbans where he had just constructed a mud cottage for Help Tourism, a Siliguri-based tour company that owns Sundarbans Jungle Camp resort in the delta region. It was a two-room cottage made of natural, sustainable materials such as mud, bamboo and stone tiles, with the roof made of khapra, curved clay tiles commonly found in Jharkhand. I was amazed by how he had modelled a traditional mud house for a modern lifestyle. I didn’t know it was really possible. Modern does not have to be industrial, Bidyut-da, told me then as he emphasised on the need to promote natural materials for construction. I wrote about the project on New York Time’s India Ink blog.

Later, my husband and I met him and his wife Lipi Biswas at their home in Santiniketan. It is a lovely mud house, like the typical clay-and-bamboo village homes of south Bengal; and I remember it being an artistic haven. The delightful Lipidi is a potter and ceramic artist who shapes clay and ideas in the workshop that sits right at the front of their home. I was blown over by how everything they did was so artistic, experimental, non-conformist and yet delicate. We went back again, with our friends, to see them during our subsequent trips to Santiniketan, where my parents-in-law live.

Having carved a niche for himself as an architect of artistic eco-friendly cottages in south Bengal, Bidyut-da is now gaining quite a following in the north of the state. This is evident in the fact that he is currently building a retreat for wellness and mindfulness–a project of the legendary footballer Bhaichung Bhutia at Pahargoomia, about 15 km from Bagdogra airport. Envisaged by the footballer and Dr Bina Basnet, an environmental and political activist who is also a champion of wellness and mindfulness, the retreat, I hear, is going to be a hub of activity and will come up alongside a football academy. But more on that later, in a separate post. This post I dedicate to Bidyut-da, the quiet rebel who is gently reshaping our ideas of home, beauty, and the very way we choose to live on this earth.

Just after the Pujas this year, the husband and I tagged along with Sujatadi, our friend (you may remember her from my earlier posts), who is very close to both Bidyutda and Lipidi and descended upon Paharagoomia. The stretch from the highway to the project site, through lush green tea gardens, made for a back breaking ride on an e-rickshaw, but the sight that awaited us at the end made every jolt worth it.

Set against the deep blue autumn sky was this striking beauty, its red khapra roof glowing warmly in the sun. The clay lattice along the verandah, the black-and-white murals, the ceiling lined with hogla leaves, the cool blackstone floor, and the mud-plastered walls burnished by hand—all of it came together with an arresting beauty that my photographs can only hint at.

What strikes you first is the absence of colour. Everything is black, white, or in varying shades of grey; only the roof brings in terracotta. The colour, instead, comes from the surroundings—from the lush green tea garden, the pollution-free blue sky and the changing light. Bidyut-da isn’t one for overusing colours. “I like things in black and white,” he told me. “It signifies something certain, something decisive. Colours feel like indecision, as if you’re not sure of yourself.”

As someone who dwells in the greys, I am not a big fan of being so sure, but I like Bidyut-da’s conviction. I like the fact that so much thought has gone into the process of creating that building, that the art and architecture is not random, but rooted in intention. Nothing is decorative for the sake of it; every line, material and motif carries a reason, a memory, or a principle. Even if I may not share his certainty, I appreciate the clarity with which he builds—quietly, purposefully and without compromise.

Bidyut-da serves us biscuits and bhujiya on fresh green leaves, along with black tea. It immediately takes me back to a meal at his Santiniketan home, cooked in Lipidi’s clay pots and served on clay plates. At the end of that meal, their nine-year-old daughter had arranged mishtis of alternating colours on small leaves she had collected, turning an ordinary tray into something unexpectedly charming. I was amazed. The last time I had eaten from a leaf was as a child playing bhanda-kuti.

This is the thing about Bidyut-da: he makes you question why we complicate our lives, why we reach for modern conveniences even when they aren’t necessary. He reminds us that simplicity can be beautiful, and that being artistic doesn’t require excess.

He also nudges you to rethink familiar routines. “Do we have to cook certain things in a certain way?” he asked, describing the food experiments he tries with his daughter. “Why not cook something new, change the regular recipe, try a spice you’ve never heard of, mix this with that?” I remembered the kolmi saag greens we once had at their Santiniketan home, cooked in an East Asian style—a small rebellion on a plate. At the heart of art lies this spirit of questioning, breaking norms and challenging conventions. My rebellious heart loves this.

The same applies to buildings. High-rises and modern structures are a reality we cannot escape; of course we need to move with the times. But that doesn’t mean everything has to look and feel the same. We can do things differently. We don’t need to abandon traditional practices altogether. Wherever possible, we can choose natural materials and alternative ways of building. “I can’t build high-rises with mud and bamboo,” he told us, “But I can build small homes with natural materials. There should be space for this kind of work too.”

Considering that construction is one of the major contributors to pollution in India, there should be a policy push towards promoting alternatives using natural materials, drawing on traditional knowledge systems, and encouraging low-impact building practices. These approaches won’t replace large-scale construction, but they can certainly coexist, offering healthier, more sustainable options where they make sense.

The second round of tea had been gulped down, and we were winding up our adda when in walked who else but Bhaichung Bhutia and Dr Basnet, who were there to assess the progress of the building. Soon enough, the inevitable question came up—what should the wellness retreat be called? As always when you’re choosing a name, there was plenty of laughter and many possibilities thrown around. I have a feeling they did settle on one, but it isn’t for me to reveal; I’ll leave that announcement to them. I look forward to catching up with them again to hear more about the project, which I’ll tell you about in a later post.

For now, I leave you with some pictures.