Cafe the Twins and Chhimeki collaborate to organise Analogue Connect monthly, a unique initiative to promote digital detox.

Earlier this month, I found myself on a rather unusual panel at Analogue Connect, a monthly gathering at Café the Twins in Salbari, aimed at digital detox. (Aside: This café, run by my dear friend Lekha, is my favourite haunt, you may know by now.) The event is a collaboration between the café and Chhimeki, a voluntary organisation led by Abhay and Smriti, who are also my friends, and who work on promoting social health.

The idea behind Analogue Connect is simple yet radical—freewheeling conversations without the tyranny of mobile phones. At the start of the programme, we tuck our devices into a tiny wooden bed, as if to put them to sleep, and then we engage in conversations– real, meaningful. To lead the conversation are a few “human books” (because every human being is a book in herself), or talking heads, who have been invited to share their stories and ideas that have shaped their lives.

That evening, my husband Nikhilesh and I were humbled to be a part of this eclectic collection of books alongside author Chuden Kabimo and retired teacher and cultural activist Nilamani Thapa. If Nilamani guruama gave us goosebumps with her memories of the Gorkhaland andolan, or the agitation, of the late eighties, Kabimo’s story of becoming an author was nothing short of a masterclass on writing.

With my phone fast asleep, I couldn’t record the conversations. But I had taken it upon myself to interpret the speeches for the benefit of the multi-lingual audience, and so scribbled notes as the others spoke. Those notes have come to my rescue now, as I try to put down what Kabimo said about writing—insights that aspiring writers might find helpful.

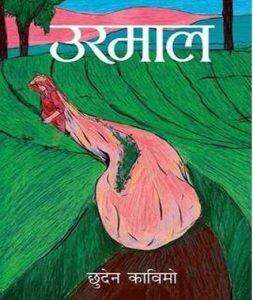

And what better moment to write this than now? Just about a week ago, news came in that Kabimo had won the Madan Puraskar for his latest book Urmal. The Madan Puraskar, often described as the Booker Prize of Nepali literature, is Nepal’s most prestigious literary award, presented each year to the most outstanding book in the Nepali language. That Kabimo is only the second Indian to win it is no small matter. But before I get to Urmal, let me trace the journey that brought him here.

Born in 1989 in a remote village in Kalimpong, Kabimo grew up at a time largely untouched by the internet or even television. “Even to see a car in the village was a big deal,” he said with a laugh. It was a life shaped by what he calls the “simple joys of rural living.”

As he tells us, Kabimo never consciously set out to become a writer. But three essential skills he picked up as a boy shaped his writing career without him realising it. Of course, when you want to become a writer, you must write. But in order to be able to write you have to develop some key skills: listening, reading, and imagining.

The nineties, as we all remember, was still a time when people listened. They listened to the radio, and they listened to each other. More so in Kabimo’s village where, in the evenings, villagers gathered and exchanged stories. A child among them, Kabimo listened out of habit until it became a skill. “Later, when I began research for my writing and interviewed people, my ability to listen carefully—to understand and interpret their stories—proved invaluable.” Kabimo said sometimes the people he interviewed would get carried away with their outpourings, beyond the scope of his research. His listening ability not only made his interviewees open up, but also helped him note important details, sometimes cloaked in digressions or casual remarks.

Kabimo started to read books when he was five, or six. He was a voracious reader and devoured anything he could lay his eyes on. The Russian masters, especially Tolstoy, left a profound impression on him. “I would cry after reading them,” he said, explaining how the classics still have the same effect on him, and this is why he revisits them every now and then. Books, however, were not easy to come by in villages with no bookshops or libraries. He managed to borrow them, somehow finding his way to books despite the odds.

Indeed, to write well, one must first read deeply. After all, every writer is shaped by the books they consume. Through the discipline of reading, the craft of writing slowly takes root.

Speaking of writing, guess where did he make a start? Letters. Yes, the good old letters. That was perhaps the last decade of letter-writing. People still wrote letters; lovers exchanged love letters. Families depended on them to stay connected across distances, and each envelope carried a little piece of someone’s world. Many from Kabimo’s village had migrated out—to join the army, to work elsewhere. He wrote letters to friends and relatives who had moved away.

In those letters began Kabimo’s journey. Who might be in possession of them now, I wondered. The thought gripped me with a sudden wish to read them. I made a mental note to ask him more about his letter-writing later. After all, I myself had been a big fan of hand-written letters; I wrote to friends and relatives, and even had a pen friend once.

Eventually, he started writing poems and short stories, which he sent to the literary pages of local newspapers like Sunchari and Himalaya Darpan. “It was for the thrill of seeing my byline on the paper,” he recalled. That thrill, as any writer will admit, can be addictive. For Kabimo, it laid the foundation for the “habit of writing,” which eventually blossomed into books. “Without my knowing it,” he said, “the life I led growing up shaped me into a writer.”

And boy did he write! What an impressive body of work he went on to create! His first collection of short stories, 1986, earned him the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar in 2018. His next book, Faatsung, was shortlisted for the Madan Puraskar the same year, and later translated into English as Song of the Soil by Ajit Baral. The English version went on to be shortlisted for the JCB Prize, bringing Nepali writing from India to the wider non-Nepali world. Faatsung has since been translated into Bengali, Hindi and English—something almost unheard of for contemporary Nepali writing from this region. Kabimo’s brave explorations of the Gorkhaland movement and its lingering wounds have breathed new life into Nepali literature from India. And then came Urmal, the book that has won him the Madan Puraskar, placing him in a league of his own.

We all could have gone on listening to Kabimo, but time, as always, was running out. Towards the end, he quoted George Bernard Shaw: “Both optimists and pessimists contribute to society. The optimist invents the aeroplane, the pessimist the parachute.” Making a case for different ways of seeing. Every perspective has its place in shaping the world.

“There’s no wrong way or right way. Just write,” he said wrapping up his talk and then left us with a line that lingered long after the evening ended: “What you must hold on to is… imagination.”

And in all this, I forgot to ask him about those letters.

All photographs are by Analogue Connect.